“It is too late, for the pixels have claimed me…”

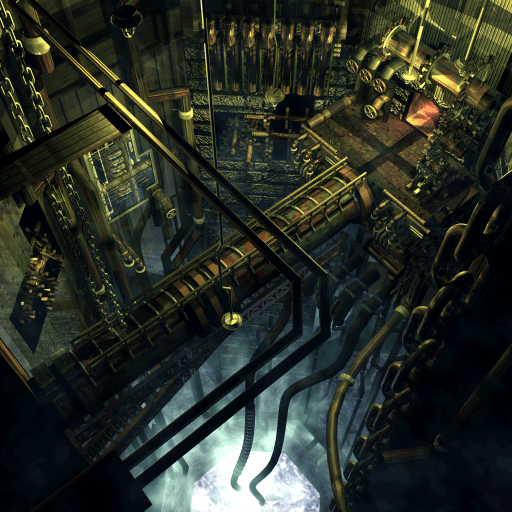

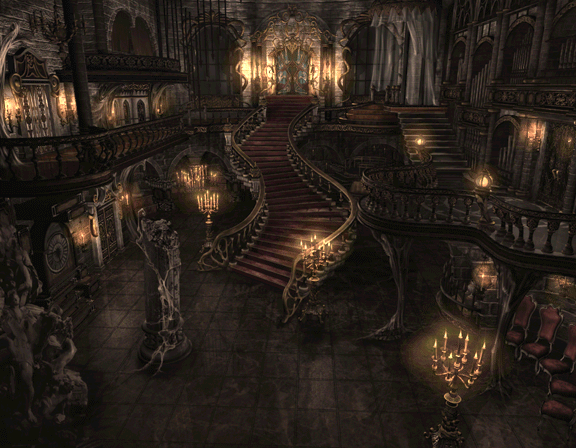

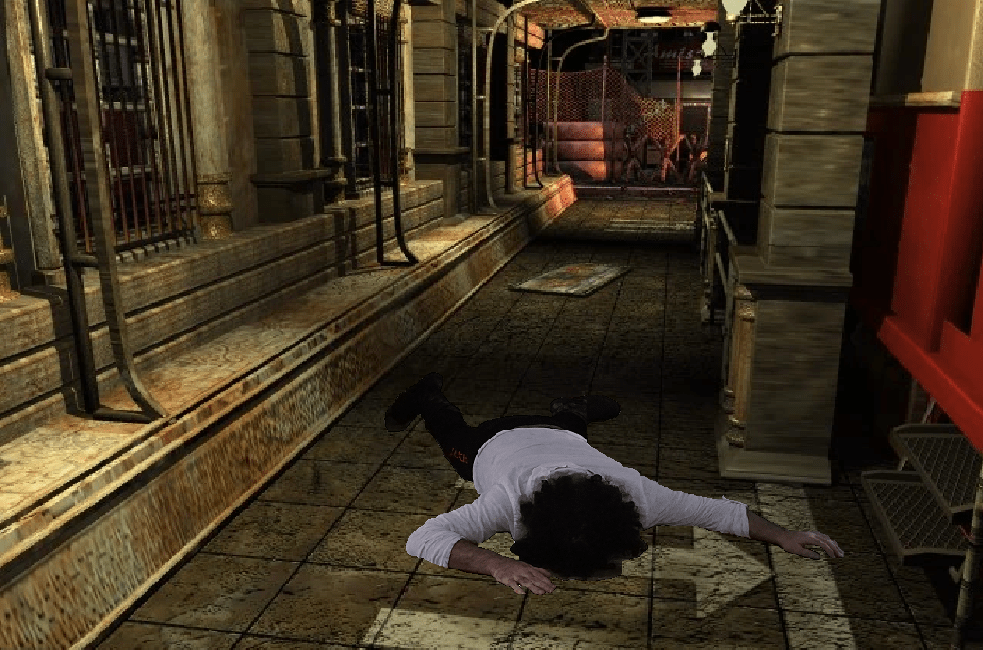

I was born and raised in the Playstation era. Blocky, sharp polygons were my bread, pre-rendered backgrounds my butter, and the Playstation was my home away from home. When I recall those simpler times when gaming felt “magical and illusionary,” my mind immediately jumps to those traversable digital backgrounds. The details, the atmosphere, and every location had a way of feeling “alive.”

Worlds connected by digital portraits, where your imagination can fill in the blanks. They craft an illusion of scan lines and polygons, but most of all, fun. But as technology does, it leaves things behind, and it wouldn’t be long until proper 3D environments became the norm. Pre-rendered backgrounds, while not a lost art, are unneeded by today’s standards. Games today can effortlessly sell you the grandiosity of the world they present, allowing players to interact with it however they please.

The world is there, so go explore it!

I love big open worlds, and I wouldn’t trade the freedom granted by this power for anything, but a few questions remain that irk me: When and how does a game’s world “feel” big? How detailed does it need to be? Is there a point where there is nothing more to see? The answer is up to preference and best discussed in its own post. For now, let’s admire pre-rendered backgrounds a little more and how they’ve evolved over the years.

From Computer to Canvas:

As I’ve said, pre-rendered backgrounds are not a lost practice. Two notable examples of recent memory are 2015’s Pillars of Eternity and 2019’s Disco Elysium. Although I haven’t played either game, I do admire their usage of the technique. All of the images I’ve shared thus far are computer-generated, but it’s important to note that they don’t have to be. I remember 2012’s Bravely Default and its gorgeous watercolor backgrounds:

If I could frame every portrait of that game, I could open my own gallery. To insinuate not just a sense of the fantastical but also a familiar one. My favorite video game, 2008’s The World Ends With You (TWEWY), uses the real-life setting of Shibuya and distorts it to create something familiar yet highly stylized:

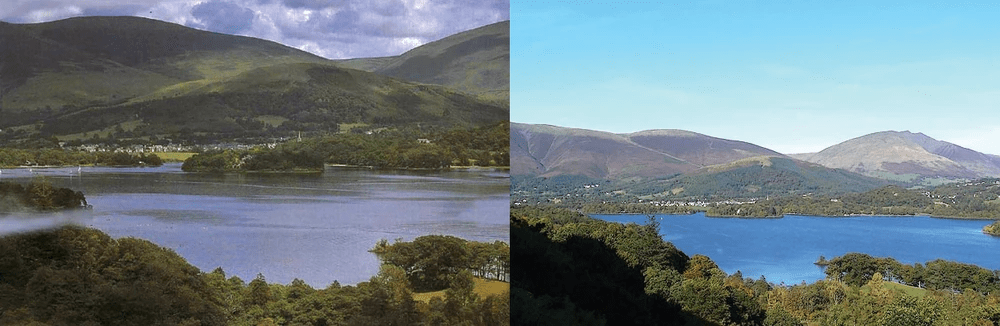

If you play the game and then visit the city, it becomes impossible to not be awestruck by the attention to detail. We’ve walked the same streets, touched the buildings, and felt the culture, even if the world in the game is a partial recreation. A truly unforgettable world gives players the right amount of details so their minds can do the rest. Now, our world is very unique and varied, and I have seen games that use photos of actual locations in clever ways:

Right: Derwentwater (England)

However, there is a dichotomy where our world falters, and pre-rendered images fall short. Why make your world from photos when you can just make fully rendered three-dimensional models? In these instances, the games have to distort our reality somehow. If TWEWY used actual pictures of Shibuya and made a game on top of it, it would undoubtedly break the illusion. On the other hand, if someone actually scanned the city and recreated it digitally, TWEWY would lose a lot of its charm. There must be another way, another edge… This may sound crazy, but what about dioramas?

From Canvas to Actual Dirt:

Developed by Mistwalker and released in 2021, we have Fatasian, the “Diorama Adventure RPG.” I’m somewhat familiar with their work, namely, the EXTREMELY underrated- The Last Story. A game so intrinsically British that you may mistake it for Xenoblade’s long-lost relative. While I never played Fantasian, since I’m poor and don’t own any Apple products, I cannot begin discussing it without mentioning the man behind it—the father of Final Fantasy himself, Hironobu Sakaguchi. The legend whose work helped bring so many of those classic computer-generated backgrounds to life and Fantasian isn’t anything like his previous outings. Instead of computerized images or grandiose drawings, it presents its world using 3D-scanned dioramas. The results speak for themselves:

Credit@ RPGFan – Mistwalker

Everything looks and feels solid. Like you can touch and feel it… because you can. Its mere existence challenges what 3D graphics could be. Each location has what I can assume to be hours of blood, sweat, and personality within each of their carefully crafted and placed props. Of course, since the environments are fully 3D, they technically don’t fall under the definition of pre-rendered, which solely uses 2D imagery. It’s cheating, in a sense, and it achieves it with the camera. Fantasian’s camera recreates the perspective of those classic RPGs we all know and love while dynamically shifting to reveal every detail of the set. The old and the new come together, and because of this, a level of seamlessness can be felt while playing.

The world shifts, and ebbs with your movements, and the loading screens take you from one diorama to the next. Exploring them is like moving imaginary toys across a world you tower over, akin to a DM. In some ways, it is similar to an AR game, where digital assets are layered atop the real world—in this case, miniature sets. Over 150 dioramas were made, and in a comment made to IGN, Sakaguchi described the process as thus:

“Once you lock that design in, you create this, there is no ‘hey let’s move this path over this way’ or ‘hey let’s add some more trees over here…We have to spend extra time in the concepting phase. You’re really kind of committed to that environment, and it shifts the kind of workflow, in a way.”

Sakaguchi 2021, Final Fantasy Creator Talks About His Latest RPG Fantasian and the Diorama World in Which it Inhabits

Clearly, this design process is only for those with a true passion for their craft. I boldly claim that there is no passion like a game developer’s. How they play around with technology in ways nobody could have thought of. How they can make art with the most technologically primitive software and hardware. It’s unmatched, especially with the following detail I will share. If you, dear reader, head to Mistwalker’s website, you’ll find one particular bit of behind-the-scenes footage of an actual explosion destroying a sculpture:

Credit@ Mistwalker

This detail is important to me because visual, practical effects are an unseen rarity in video games. Sakaguchi himself calls it “a game that shouldn’t exist.” And yet, here it is, a one-of-a-kind game between reality and the digital world. Accompanied by the legendary musical talents of Nobuo Uematsu, it brandishes the memory of the old Final Fantasy games while having its own identity. It’s not entirely virtual or real. Strange and experimental, as any work of art should be. There will probably never be another game like it, but after seeing it, I hope it happens again. Heck, when the game’s all done and published, throw down the dice and create a DND campaign!